Kerman Rugs

Kermans are the honor and prestige of

Persian Rugs, just like the land of Kerman

that is an honor for Iran as a living museum.

Stone carvings, Jiroft, 5000 B.C

Kerman: The citadel of Arg-e Bam, (sixth to fourth

centuries BC)

Stone carvings, Jiroft, 5000 B.C

From the very beginning of the Written

History the region has been mentioned under

the name of Aratta by Sumerians (according

to some rather persuadable theories about

that far ancient civilization). Sumerians mentioned Aratta as a wealthy

land hard to reach full of precious stones and

with great artisans to use them. A land Inanna

comes from; the goddess of love, desire and

beauty.

Actually the Jiroft-culture remains in the

Kerman province tell us about a wealthy

early Bronze Age civilization, located between Mesopotamia and Indus Valley

Civilizations.

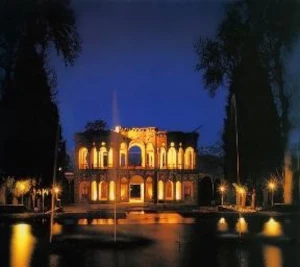

Shazdeh Mahan Garden

Still hard to reach, the land continued its

importance under the name of Carmania in

more clear parts of the ancient history as an

Achaemenid satrapy, and the name continued

its presence through the history till now in

New-Persian: Kerman. The land of rich

mines, exquisite crafts and great artisans.

Home to the goddess of beauty who walks on

embroidered rugs.

The city of Kerman had been a shawl

weaving center for centuries. It is known that

the Safavid Shahs of Persia had established

some of their royal rug workshops in Kerman, (what has remained from 17th and

18th centuries are today the most celebrated

pieces of the so-called Islamic Arts by

museums and auctions, including the two

first record-breakers of the category), but it

wasn’t until the 19th century that Kermani

weavers shifted totally from shawls to rugs

and made a turning point in the Persian rug

history.

The gifts ShahAbbas sent to the Serenissima court

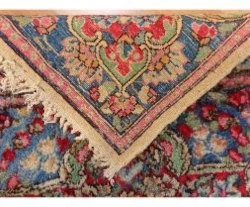

Kerman's Patteh

Museum of Zoroastrians

Kerman Embroidered Shawl

Technical aspects and the structure of Kerman Rugs

Kerman rug, rear side: white strings are thick wefts,

red strings are knots

Antique Kerman rug, rear side

Today what we call Kerman rugs are mostly

city-woven pieces made in the workshops of

Kerman and towns around from which Ravar

should be mentioned as the most important

name after Kerman itself, which is

unfortunately famous in English with a

corrupted spelling: Lavar. Experts categorize

‘Lavars’ roughly as the finest Kermans.

Kerman knots are asymmetrical (Persian) and

triple-wefted. The finest pieces’ knot count

reaches to 510,000/m2. Warp and weft are

cotton and pile is woolen.

Antique Kermans were benefited from Kork

(also known as Kerman wool) which is the

most special Iranian textile raw material. It is

a fine and thin but not fragile hair sheared off

a breed of goat native to Kerman. Shearing

must be done in spring and just the soft hair

of inner layers are gathered as kork.

For centuries kork was used for warm shawls

and fine courtly rugs but during 19th century,

with the increased demand for Kerman rugs,

it became an essential raw material for fine-

woven rugs, in both Ravar (Lavar) and

Kerman. Using kork made Kerman’s

weavers able to apply tiny curvilinear

patterns in their detailed designs without

losing the needed strength.

Dyeing and painting of Kerman rugs

Color palette used in Kerman rugs

Arjomand rug-weaving factory in Kerman is one of

the most well-known which has made some of the

royal rugs

Kerman’s master dyers and painters have a

vital role in the fame Kerman rug gained.

Their wavering colors touch deeply the

viewer’s soul.

Indigo, cochineal, walnut, weld,

pomegranate, vine leaves, straw, and henna

are some natural dyestuffs by the use of

which Kermani masters make uncountable

tones and shades ideal for loom-drawing

painters to create their magnificent pastel

colorings. To obtain a level hue, master dyers

dye the wool before spinning.

Kerman’s reddish tones are remarkable being

obtained mostly from cochineal and not

madder which is used in Heriz or other parts

of western Iran.

Designs and patterns of the Kerman rugs

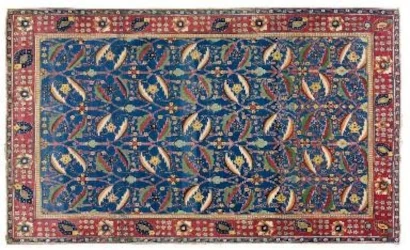

Kerman rug, Safavid period, sold at Christie’s

auction

Master designers of Kerman are da Vincis

and Michelangelos of the Orient. They were

the very first rug designers who put their

signatures on rugs, celebrating their personal

creativity. They have influenced not only

other Iranian designers (such as designers

from Yazd, Isfahan and Khorassan) but also

Indians, Pakistanis, Afghans and Romanians.

Most of basic Persian designs have their

Kerman’s interpretations. Actually some of

them are believed to be originally from

Kerman, like vase design. Repeating

patterned designs are favored. Both central

and all-over medallion designs are woven,

the latter mostly for western markets.

Kerman rug, Safavid period, known as Sickle-leaf

sold at Sotheby’s auction

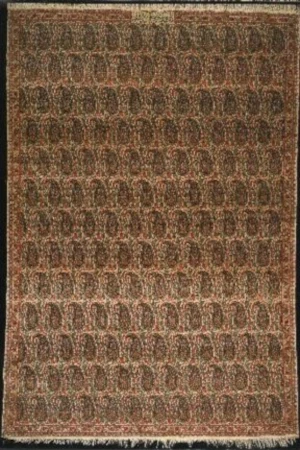

Kerman (Rāvar) rug, repetitive pattern, botte design,

19th century

Botteh, which is an ancient Iranian motif, has

been derived mainly from Kerman shawls,

being adopted to lots of woven goods. Although wide in range, Kerman designs

have a strong feature in common: being fully

floral. Every branch of a tree in a prayer

design (or every spray of a bush in a vase

design) is covered with flowers, leaves and

blossoms. Finding empty spaces between

patterns is literary a difficult task. Even

pictorial rugs enjoy detailed floral patterns on

their margins.