Shekârgâh: Hunting Garden Rugs or Hunting Rugs

Hunting is the most primitive subject in human being’s iconography, as it is apparent on prehistoric parietal arts, and thus the most ancient and ever-lasting traceable theme in historical eras, too.

‘Shekârgâh’ meaning in Persian ‘chase’, or ‘hunting garden’ is a long-lived theme in the Persian arts and a matter of interest in Persian epic poems as hunting has been a regular exercise for the Shahs of Persia.

The word ‘shekâr’ refers to both hunting and preying, and Shekârgâhs depicted on walls, vessels, miniature paintings and rugs include scenes of predators preying on other animals as well as wild animals and games being hunted by humans, mostly mounted kings and heroes accompanied by greyhounds, cheetahs and birds of prey.

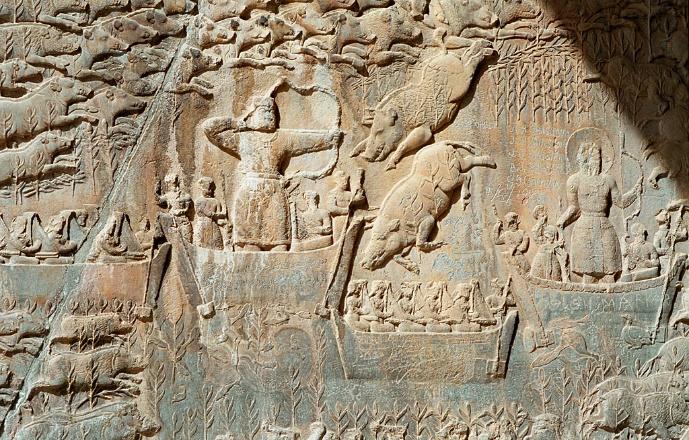

In the Mesopotamian parts of their territories, the Achaemenid kings had succeeded Assyrians whose reliefs with hunting scenes are amongst the most magnificent ancient works of art. These reliefs represent the Assyrian kings as the slaying warriors in front of rebellious folks as well as triumphant hunters against lions in their fanciful hunting gardens. (Pic1)

Despite adopting the art, the Achaemenid kings showed much less interest in the ‘killer king’ theme on their walls and rocks, which could be probably a proof of their Zoroastrian orthodoxy. Darius the great and his offspring depicted themselves in the dignified stature of a king who rest in peace, while nobles from all over the kingdom gather willingly to celebrate his throne. Amazingly, they didn’t either show much tendency to depict themselves as animal killers. There are of course seals with ‘the hunting King’ icon but Shekârs in Achaemenid art were based mostly on preying scenes.

These vary from stylistic reliefs with certain symbolism (Pic3) to vivid sculptural rhyta which evoke the vitality and boldness of preying (Pic4).

It was not until the Sasanid Era that hunting became a most favored theme in Iranian arts. There exist examples of pure talent and artistry on bronze, silver and golden plates, depicting Persian Shahs such as Khosrau and Bahrâm the Gur, slaying boars and lions with sword, javelin, lasso and bow.

The epithet Gur, meaning namely swift, is the Persian appellation for what is called in western languages Persian onager, Persian wild ass or Persian zebra; a fast runner inhabitant of plains, mountains and deserts. Bahram the Gur (-chaser or the Swift) is a well celebrated Shah in the Iranian folklore as well as in the classical Persian literature; a character for fairy tales and ballads in all of which he reveals his dexterity and swiftness. In Nizami Ganjavi’s Haft Paykar (the Seven Idols or the Book of Bahram) Bahram proves his right to the Sasanid crown through catching it from two ferocious lions. (Pic5)

Another Sasanid Shah with similar legendary reputation is Khosrau Parvez whose royal hunt has been carved marvelously on a rock in Taq-e Bustan; maybe the most renowned Shekârgâh in the Iranian art history. This valuable historical source shows a large-scale boar hunt with royal expedition including two figures of the Shah himself with bow, attendants, beaters, musicians, elephant riders and oarsmen. (Pic6)

The Sasanid Shahs have remained frequent subjects of hunting scenes during Islamic period through illustrations of Ferdowsi’s Shahnama (the book of the kings) and Nizami Ganjavi’s Khosrau and Shirin and Haft Paykar. The theme flourished in Timurid and Safavid courts in Herat, Tabriz, Qazvin and Isfahan by great masters such as Mirak, Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād and Sultan Mohammad the Painter.

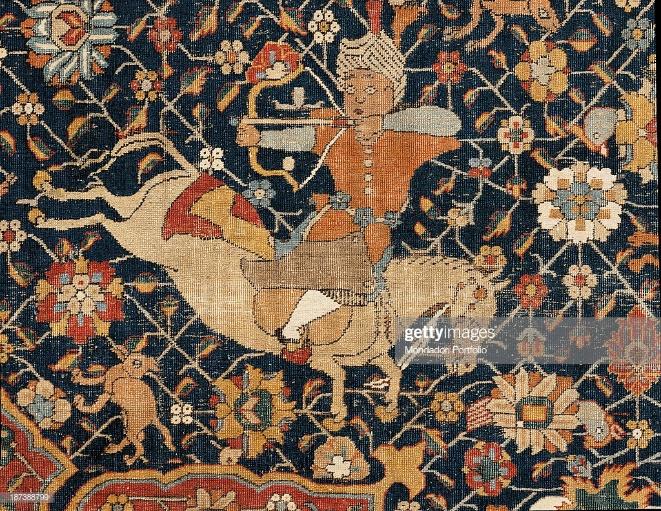

These great painters are also considered as rug designers of the Safavid royal workshops in which Shekârgâh was adopted vastly as rug designs. Accordingly, the style and the rendering of figures has come directly from the royal library into the hunting rugs.

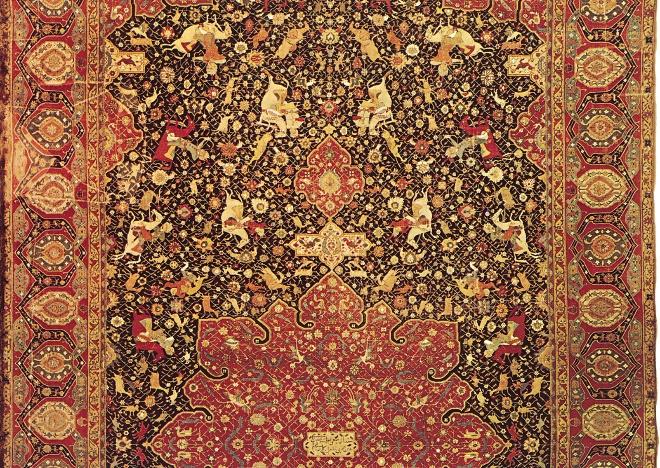

These workshops used to produce fine-woven pieces as royal gifts given at formal occasions to princes and generals as well as ambassadors and foreign kings. Some of these pieces have artist’s signature that should have been an innovation for the time; like the one in Poldi Pezzoli Museum, Milan, Italy which has an Islamic date equivalent of 1542 AD and a Persian inscription in verse right in the heart of its central medallion, reading: “with endeavor of Ghiāth ud-Dīn Jāmi, this renowned deed is done goodly.”

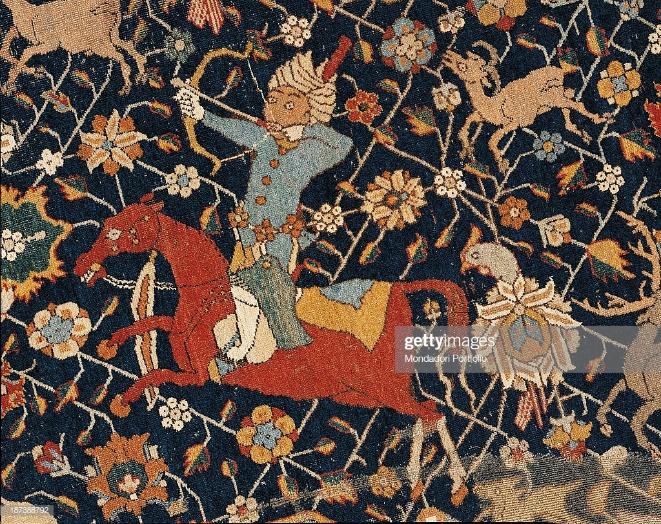

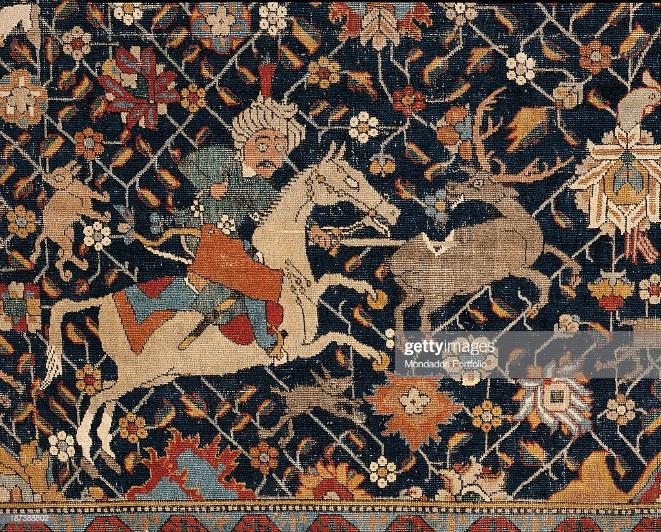

Indeed Ghiāth ud-Dīn Jāmi has done well. Birds fly in the large vermilion central medallion which has quartered the midnight blue field in which mounted hunters, lions, boars, gazelles and foxes have been arranged amongst intricate floral patterns that glow like tiny stars in a midnight sky. The hunters thrust their spears at boars and lions; gazelles run in pairs, ducks and fish swim in the ponds, and a lioness prey on a human! (Pic8)

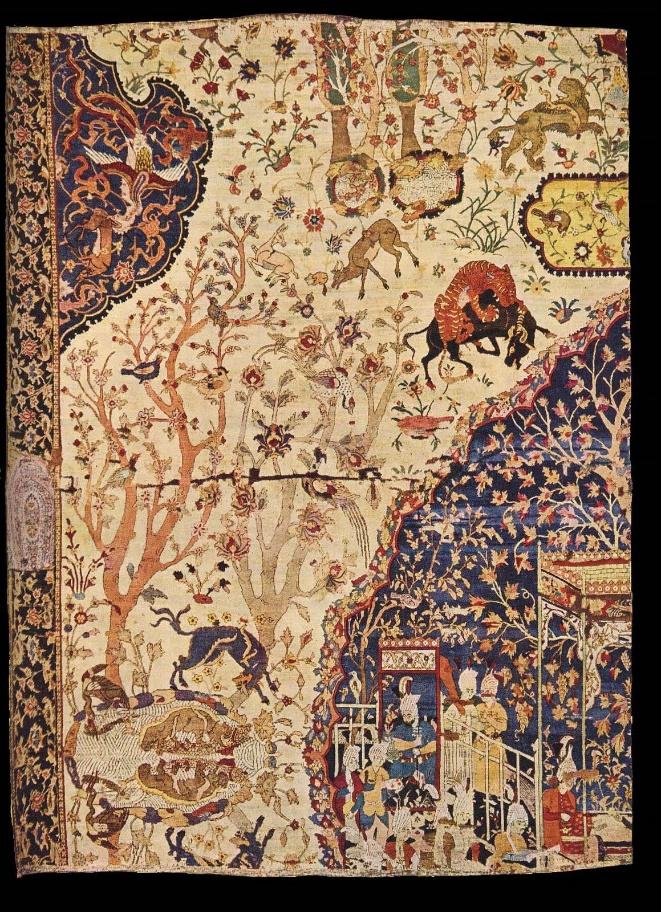

Another famous examples are sixteenth-century silken pieces in the Royal Palace in Stockholm, Sweden and Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Vienna, Austria. In the ‘Swedish’ one there is a central star medallion, filled with what is called ‘dragon and phoenix’ motif which could point out a Chinese influence. Its field is occupied by mounted hunters pursuing various animals. On the Austrian one there are dismounted bowmen as well as mounted ones targeting and pursuing animals on a khaki field with a minimal medallion in a humble tone not being visible at the first glance. Opposite to the khaki, a crimson margin frames the field like walls on which sit angels handing each other cups of wine. An actual ‘paradise’ which indeed means in the Ancient Persian ‘walled-garden’.

The excellence of these royal carpets made the Safavid style the predominant interpretation of Shekârgâh. Which is a well stylized version of the theme. In the following centuries such designs were imitated in the Indian Mughal Court as well as Iranian city-workshops in Kashan and Tabriz. These cities have still kept the designs alive. The designs could be arrange in both central-medallion and all-over settings, detailed or not, with scenes of hunting, preying or both, mostly woven fine and dense with wool and silk threads.

In the absence of reliefs, golden plates or royal illustrated books, carpets have become the main medium of art in which the long-lived theme of Shekârgâh continue to exist.